Technology

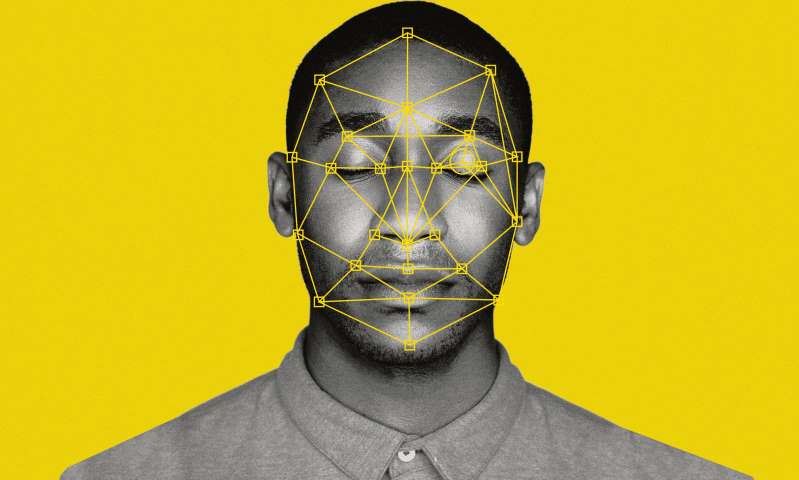

What is facial recognition?

Facial recognition technology has spread prodigiously. It’s there on Facebook, tagging photos from the class reunion, your cousin’s wedding and the office summer party. Google, Microsoft, Apple and others have built it into apps to compile albums of people who hang out together.

It verifies who you are at airports and is the latest biometric to unlock your mobile phone where facial recognition apps abound. Need to confirm your identity for a £1,000 bank transfer? Just look into the camera.

New applications crop up all the time. Want to know who’s at the door? A video doorbell with facial recognition will tell you, provided you’ve uploaded a photo of the person’s face. Other systems are used to spot missing persons and catch slackers who lie about the hours they spend in the office. Advertisers, of course, are in on the act. Thanks to facial recognition, billboards can now serve up ads based on an estimate of your sex, age and mood.

That sounds quite Big Brother. Is it a surveillance tool?

Sometimes, yes. China uses facial recognition for racial profiling and its tracking and control of the Uighur muslims has been roundly condemned as a shameful first for a government.Its cameras also spot and fine jaywalkers, verify students at school gates, and monitor their expressions in lessons to ensure they are paying attention.

Russia has embraced the technology too. In Moscow, video cameras scan the streets for “people of interest” and plans have been mooted to equip the police with glasses that work the same way.

There have been reports that Israel is using facial recognition for covert tracking of Palestinians deep inside the West Bank. Meanwhile in Britain, the Metropolitan and South Wales police forces have trialled facial recognition to find people in football and rugby crowds, on city streets, and at commemorations and music festivals. Taylor Swift even installed the tech at a gig in California to weed out stalkers.

Shops are increasingly installing the technology to deter and catch thieves. Next year, it will make its Olympic debut in Tokyo.

How did it get everywhere?

Advances in three technical fields have played a major part: big data, deep convolutional neural networks and powerful graphics processing units or GPUs.

Thanks to Flickr, Instagram, Facebook, Google and others, the internet holds billions of photos of people’s faces which have been scraped together into massive image datasets. They are used to train deep neural networks, a mainstay of modern artificial intelligence, to detect and recognise faces. The computational grunt work is often done on GPUs, the superfast chips that are dedicated to graphics processing. But there is more to it than flashy new technology. Over the past decade in particular, facial recognition systems have been deployed all over the place, and the data gathered from them has helped companies hone their technology.

How does it work?

First off, the computer has to learn what a face is. This can be done by training an algorithm, usually a deep neural network, on a vast number of photos that have faces in known positions. Each time the algorithm is presented with an image, it estimates where the face is. The network will be rubbish at first, like a drunk playing pin the tail on the donkey. But if this is done multiple times, the algorithm improves and eventually masters the art of spotting a face. This is the face detection step.

Next up is the recognition part. This is done in various ways, but it’s common to use a second neural network. It is fed a series of face pictures and learns – over many rounds – how best to tell one from another. Some algorithms explicitly map the face, measuring the distances between the eyes, nose and mouth and so on. Others map the face using more abstract features. Either way, the network outputs a vector for each face – a string of numbers that uniquely identifies the person among all the others in the training set.

In live deployments, the software goes to work on video footage in real time. The computer scans frames of video usually captured at crowd pinch points, such as entrances to football stadiums. It first detects the faces in a frame, then churns out vectors for each one. The face vectors are then checked against those for people on a watchlist. Any matches that clear a preset threshold are then ranked and displayed. In the British police trials a typical threshold for a match was 60%, but the bar can be set higher to reduce false positives.

It’s not the only way the police use facial recognition. If a suspect has been picked up, officers can upload their mugshot and search CCTV footage to potentially trace the suspect’s movements back to the scene of a crime.

How accurate is it?

The best systems are impressive. Independent tests by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (Nist) found that between 2014 and 2018 facial recognition systems got 20 times better at finding a match in a database of 12m portrait photos. The failure rate fell from 4% to 0.2% over the period, a massive gain in accuracy that was largely down to deep neural networks. Nist says the networks have driven “an industrial revolution” in facial recognition.

But such great performance depends on ideal conditions: where a crisp and clear mugshot of an unknown person is checked against a database of other high quality photos. In the real world, images can be blurred or poorly lit, people look away from the camera, or may have a scarf over their face, or be much older than in their reference photo. All tend to reduce the accuracy.

The technology has a terrible time with twins, the Nist tests found, with even the best algorithms muddling them up.

What about bias?

Bias has long plagued facial recognition algorithms. The problem comes about when neural networks are trained on different numbers of faces from different groups of people. So if a system is trained on a million white male faces, but fewer women and people of colour, it will be less accurate for the latter groups. Less accuracy means more misidentifications and potentially more people being wrongly stopped and questioned.

Last year, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) found that Amazon’s Rekognition software wrongly identified 28 members of Congress as people who had previously been arrested. It disproportionately misidentified African-Americans and Latinos. Amazon said the ACLU had used the wrong settings.

Police trials have highlighted further shortcomings of facial recognition. A Cardiff University review of the South Wales trials found that the force’s NEC NeoFace system froze, lagged and crashed when the screen was full of people and performed worse on gloomy days and in the late afternoon because the cameras ramped up their light sensitivity, making footage more “noisy”.

During 55 hours of deployment the system flagged up 2,900 potential matches of which 2,755 were false positives. The police made 18 arrests using the system, but the Cardiff report does not state whether any of the individuals were charged.

The Welsh trial highlighted another challenge for facial recognition: lambs. Not farmyard fugitives but people on the watchlist who happen look like plenty of other people. While scanning the crowds at Welsh rugby matches, the NeoFace system spotted one woman on the South Wales police watch list 10 times. None of them were her.

Who has the technology?

Tech firms around the world are developing facial recognition but the US, Russia, China, Japan, Israel and Europe lead the way. Some nations have embraced the technology more readily than others.

China has millions of cameras connected to facial recognition software and Russia has declared hopes to expand its own surveillance networks. In Europe, as elsewhere, facial recognition has found its way into shops to spot thieves and into businesses to monitor staff and visitors, but live face recognition in public spaces is still mostly at trial stage.

In the US, the police typically use facial recognition to search CCTV footage for suspects rather than scanning live crowds. But it is becoming more pervasive. A 2016 report from Georgetown Law’s Center on Privacy and Technology found that half of all Americans are in police facial recognition databases, meaning that algorithms pick suspects from virtual line-ups of 117 million mostly law-abiding citizens.

What does the law say on it?

Not much. In Britain there is no law that gives the police the power to use facial recognition and no government policy on its use. This has led to what Paul Wiles, the Biometrics commissioner, calls a chaotic situation with the police deciding for themselves where and when it is appropriate to use facial recognition and what happens to the images the cameras capture.

The campaign group, Liberty, has called for a complete ban on live facial recognition systems in public spaces, arguing that it destroys privacy and forces people to change their behaviour. The group has brought a judicial review against South Wales police over its use of the technology. Similar concerns were raised by the University of Essex in an independent review of the Metropolitan police force’s use of facial recognition. It found that people were wrongly stopped, and warned of “surveillance creep” where the technology ends up being used to track people who are not wanted by the courts. Live facial recognition, the report concluded, was likely to fall foul of human rights law.

Another area of contention is watchlists. Despite a 2012 high court ruling that retaining images of innocent people was unlawful, the police have steadily built up a custody database of 20 million people, many of whom have never been convicted of a crime. Nonetheless, images from the database, and others scraped from social media, are used to create watchlists for use in facial recognition systems. In the private sector, the situation is even murkier, with shops and businesses deciding who goes on secret watchlists, and sharing images with other firms.

In the US the situation is not much better. Only five states have laws that touch on the use of facial recognition by law enforcement. The patchwork of laws means that while the Seattle police force and San Francisco city have banned live facial recognition, the sheriff’s office in Maricopa County, Arizona, uploaded the photo and driver’s licence of every resident in Honduras to its facial recognition watchlist.

What about other biometrics

While facial recognition technology has drawn huge attention, the police and other organisations are looking carefully at new biometrics, beyond fingerprints and DNA, that uniquely identify people.

Skin texture analysis is said to overcome problems with facial recognition caused by different expressions and partially covered faces by analysing the distance between skin pores. It has not been tested much, but developers claim it could be good enough to distinguish between twins.

Another biometric that interests the police, because it can be done at a distance without a person’s cooperation, is gait analysis. As the name suggests, the algorithms identify people by the unique style of their stride, reflecting differences in anatomy, genetics, social background, habits and personality.

With vein recognition, optical scanners are used to map blood vessels in the hand, finger or eye. Because our veins are buried beneath the skin, the scanners are considered hard to fool. Fujitsu’s PalmSecure system uses vein maps to monitor the to and fro of employees at various businesses.

Speaker recognition is already used by banks and the HMRC to confirm people’s identities and its use is spreading. Unlike speech recognition, which translates sounds to words, speaker recognition detects the unique acoustic patterns created by an individual’s vocal tract and their speech habits.

What next?

Ubiquity, perhaps. The US firm, Vuzix, has teamed up with a Dubai firm, NNTC, to produce facial recognition smart glasses. The frames hold a tiny eight-megapixel camera which scans the faces of passers-by and alerts the wearer to any matches in a database of a million people. In Britain, Wireless CCTV is working on police body cameras that do much the same thing. A recent US patent goes further and describes a police bodycam that starts recording when the face of a suspect is spotted.

Meanwhile, tech firms are improving their systems to work faster, with more faces, and with ever-more-difficult images, such as those taken in bad light or when people have their faces covered. Though still in its infancy, work is under way on algorithms that can identify people wearing masks and other disguises. To make recognition systems even more effective, face biometrics will be combined with others such as voice and gait, according to the Home Office’s 2018 Biometrics Strategy. Unsurprisingly, an arms race is afoot: researchers at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh have developed their own sunglasses to fool facial recognition: one male researcher who wore a pair was identified as Milla Jovovich.

-

Cryptocurrency7 days ago

Cryptocurrency7 days agoTop 6 Promising Cryptocurrencies for Early-stage Investments

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoIs it Good To Eat Cheese Daily? | Pros & Cons Of Eating Cheese

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days ago12 Health Benefits of Eating Raw Ginger

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days ago10 Amazing Benefits of Eating 1 Khajoor Daily

-

Money7 days ago

Money7 days agoMother’s Day 2024 : Top five buying health insurance tips for mothers

-

Money7 days ago

Money7 days agoMotherhood and Peace of Mind: Building an Emergency Fund for Expectant Mothers

-

How to2 days ago

How to2 days agoHow to Choose a Reliable Mutual Fund Distributor: A Comprehensive Guide

-

Health3 days ago

Health3 days ago5 Herbal Teas That Improve Digestion Naturally